Returning to my earlier difficulty with these lines in Robert Browning’s Pied Piper of Hamelin:

Save one who, stout as Julius Caesar,

Swam across and lived to carry

(As he the manuscript he cherished)

To Rat-land home his commentary,

The short of it is that someone is confused, though it’s impossible to say whether it is Browning, his possible source, his recent editors, or me. The trouble is Browning’s choice of words – manuscript for what Caesar carries and commentary for what the rat to which he is compared carries. This choice encourages – but does not require – understanding an equivalency between the two words (i.e. Caesar’s manuscript was a commentary) and recent editors seem to take this possibility as a given.

Accordingly the editors of the OET Poetical Works of Robert Browning (v.3, pg. 286) comment on this passage:

as Lemprière records, the Commentaries on the Gallic wars were ‘nearly lost; and when Caesar saved his life in the bay of Alexandria, he was obliged to swim from his ship, with his arms in one hand and his commentaries in the other’. The story is likely to have been familiar to Willie Macready [the boy for whom the poem was written], since selections from Caesar are often read by beginners at Latin.

The source referenced is John Lemprière’s 1788 Bibliotheca Classica: or, A classical dictionary. In his entry on Caesar Lemprière has:

The learning of Cæsar deserves commendation, as well as his military character. He reformed the calendar. He wrote his commentaries on the Gallic wars, on the spot where he fought his battles; and the composition has been admired for the elegance as well as the correctness of its style. This valuable book was nearly lost; and when Cæsar saved his life in the bay of Alexandria, he was obliged to swim from his ship, with his arms in one hand and his commentaries in the other.

The Brownings owned at least two copies of this work so it’s not unreasonable to surmise that Browning’s account derived from the source, as (I think, though it’s been a while) is demonstrable with some other references.

The Longman editors follow suit but relate the saving of the manuscript as simple historical fact:

When Caesar’s ship was captured at Alexandria, he swam ashore carrying the MS of his historical memoir De Gallico Belli [=De Bello Gallico]; such texts were known as ‘commentarii.’ Oxford notes that Willie Macready probably knew the story, ‘since selections from Caesar are often read by beginners at Latin.’

The problem here is that none of the major classical sources mention what specifically Caesar saved. Here are Suetonius, Plutarch, and Cassius Dio.

At Alexandria, while assaulting a bridge, he was forced by a sudden sally of the enemy to take to a small skiff; when many others threw themselves into the same boat, he plunged into the sea, and after swimming for two hundred paces, got away to the nearest ship, holding up his left hand all the way, so as not to wet some papers (ne libelli quos tenebat madefierent) which he was carrying, and dragging his cloak after him with his teeth, to keep the enemy from getting it as a trophy

Suetonius Caesar 64

when a battle arose at Pharos, he sprang from the mole into a small boat and tried to go to the aid of his men in their struggle, but the Egyptians sailed up against him from every side, so that he threw himself into the sea and with great difficulty escaped by swimming. At this time, too, it is said that he was holding many papers in his hand ( ὅτε καὶ λέγεται βιβλίδια κρατῶν πολλὰ) and would not let them go, though missiles were flying at him and he was immersed in the sea, but held them above water with one hand and swam with the other;

Plutarch Caesar 49

While the fugitives were forcing their way into these in crowds anywhere they could, Caesar and many others fell into the sea. He would have perished miserably, being weighted down by his robes and pelted by the Egyptians (for his garments, being of purple, offered a good mark), had he not thrown off his clothing and then succeeded in swimming out to where a skiff lay, which he boarded. In this way he was saved, and that, too, without wetting one of the documents of which he held up a large number in his left hand as he swam (μηδὲν τῶν γραμμάτων βρέξας ἃ πολλὰ ἐν τῇ ἀριστερᾷ χειρὶ ἀνέχων ἐνήξατο).

Dio Cassius 42.40

The vocabulary of these sources is all very general:

- libellus – a little book, pamphlet, manuscript, writing

- βιβλίδια – a rare diminuitive of βιβλίον (just as libellus is of liber) – with the same range of meanings as above

- γραμμάτων – plural of γράμμα – letter of the alphabet in singular; papers, documents, writings in the plural

Browning’s word choices ‘manuscript’ and ‘commentary’ are in line with any of the sources (the linked definitions provide the full range of offerings, though you sometimes need to use the non-English dictionaries to see them) so it’s not necessary to posit Lemprière as intermediary, especially if you allow for the possibility that Browning’s classical education would have naturally led him to associate Caesar with commentaries anyway. With a bit of either memory haziness or intentional poetic fudging he could reasonably have assumed or invented the equivalency on his own. He could equally well have intended no equivalency between ‘manuscript’ and ‘commentary’ and simply have been furthering the comparison of Caesar (author of commentaries) with the surviving rat (who delivers a commentary).

And then we have what started this sinkhole, the question of timeline. The tale of Caesar saving his libelli/βιβλίδια/γραμμάτα takes place in 47BCE. Modern scholarly consensus holds that Caesar’s commentaries on the Gallic wars, whether published annually or in a batch, would have been available by probably 50BCE (this is in no way my area of interest so see Kurt Raaflaub’s chapter in The Cambridge Companion to Julius Caesar for a brief summary and direction to fuller bibliography). I have no idea what late 18th century scholarship thought on this topic but I can’t help finding it very odd that Lemprière would have insisted Caesar saved his De Bello Gallico rather than the unfinished Commentarii de Bello Civile (covering years 49-48 BCE) he would’ve been more likely been working on at the time.

So all of this leaves us with the following list of possibilities:

- Lemprière follows a (for my purposes) unknown predecessor in asserting the ‘papers’ Caesar saved were his De Bello Gallico and Browning then follows him.

- Lemprière independently concludes the papers Caesar saved were his De Bello Gallico, disregarding an accepted publication timeline. Browning again follows him.

- A non-Lemprière source misleads Browning in either of the above ways.

- Browning arrives at his lines independently and mistakenly remembers the saved papers as the Gallic war commentaries.

- Browning arrives at his lines independently and implicitly presents the saved papers as the Gallic war commentaries just because the boy for whom the poem was written would have known that work over others.

- Browning arrives at his lines independently and intends the boy for whom the poem was written to understand ‘Civil War commentaries’ since he would have known that work. Modern editors lack classical education and miss the reference.

- Browning arrives at his lines independently and, a better classical scholar than his editors believed, assumed the papers were Caesar’s never-completed commentaries on the civil war. The boy’s presumed knowledge does not factor into it.

- Browning arrives at his lines independently and intends no comparison between ‘manuscript’ and ‘commentary’, just between Caesar and the surviving rat.

- This has driven me mad.

I like the last.

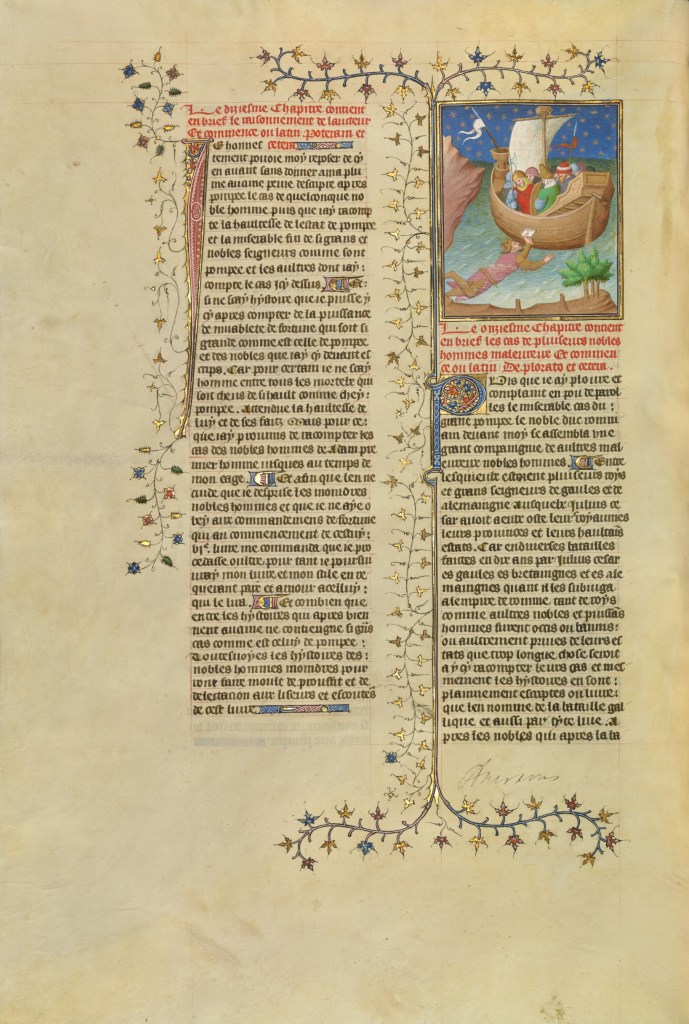

Here’s a 15th century image from the Getty of Caesar saving what a three-drink dinner encourages me to regard as a new possibility equally supported by the primary sources – a cocktail menu.