Spiralling associative chains, beginning with the Sybil to Aeneas (6.135):

Quod si tantus amor menti, si tanta cupido est,

bis Stygios innare lacus, bis nigra videre

Tartara, et insano iuvat indulgere labori,

accipe, quae peragenda prius.

In Ahl’s Oxford Classics:

Yet, if there’s love so strong in your mind, so mighty a passion

Twice to float over the Stygian lakes, twice gaze upon deep black

Tartarus, if it’s your pleasure to wanton in labours of madness,

Grasp what you must do first.

And moving to Gerard de Nerval’s El Desdichado:

Je suis le ténébreux,- le Veuf, – l’inconsolé,

Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie:

Ma seule étoile est morte, et mon luth constellé

Porte le soleil noir de la Mélancolie.Dans la nuit du Tombeau, Toi qui m’as consolé,

Rends-moi le Pausilippe et la mer d’Italie,

La fleur qui plaisait tant à mon coeur désolé,

Et la treille où le Pampre à la rose s’allie.Suis-je Amour ou Phoebus ?…. Lusignan ou Biron ?

Mon front est rouge encor du baiser de la Reine ;

J’ai rêvé dans la grotte où nage la Sirène…Et j’ai deux fois vainqueur traversé l’Achéron :

Modulant tour à tour sur la lyre d’Orphée

Les soupirs de la Sainte et les cris de la Fée.

And in the Penguin Selected Writings translation by Richard Sieburth:

I am the man of gloom – the widower – the unconsoled, the prince of Aquitaine, his tower in ruins: My sole star is dead – and my constellated lute bears the Black Sun of Melancholia.

In the night of the tomb, you who consoled me, give me back Posilipo and the Italian sea, the flower that so pleased my desolate heart, and the arbour where the vine and the rose are entwined.

Am I Amor or Phoebus? … Lusignan or Biron? My brow still burns from the kiss of the queen; I have dreamed in the grotto where the siren swims …

And I have twice victorious crossed the Acheron: Modulating on Orpheus’ lyre now the sighs of the saint, now the fairy’s cry.

And back to the beginning, a Homeric hapax from Odyssey 12.21, Circe to Odysseus:

σχέτλιοι, οἳ ζώοντες ὑπήλθετε δῶμ᾽ Ἀίδαο,

δισθανέες, ὅτε τ᾽ ἄλλοι ἅπαξ θνῄσκουσ᾽ ἄνθρωποι.Unwearying, you who alive go down to the house of Hades,

twice-dying, when other men die once.

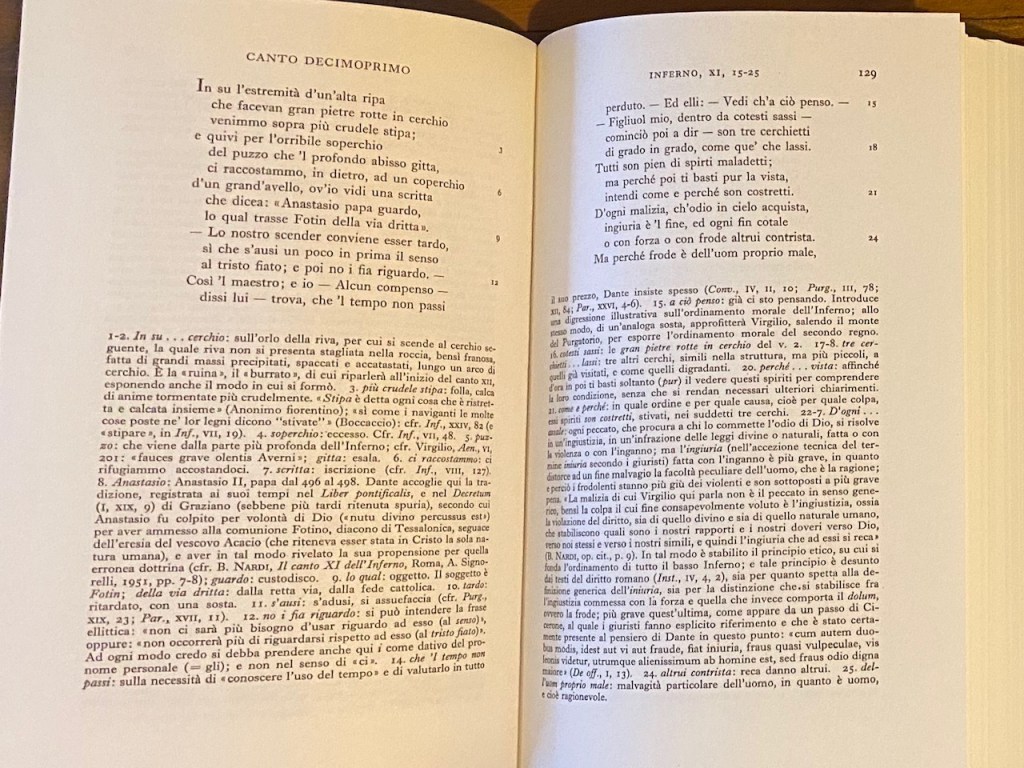

Closing with an unrelated echo from Dante, Inferno 24 4. Which commentaries tell me is also a hapax suggested by Jude’s (12) ‘arbores…. bis mortuae’ (trees twice dead).

e l’ombre, che parean cose rimorte,

per le fosse de li occhi ammirazione

traean di me, di mio vivere accorte.

And the Longfellow translation:

And shadows, that appeared things doubly dead,

From out the sepulchres of their eyes betrayed

Wonder at me, aware that I was living.