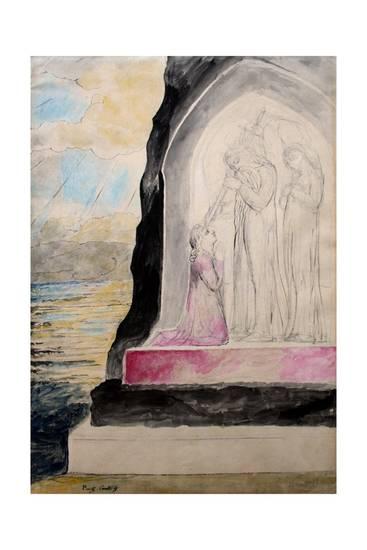

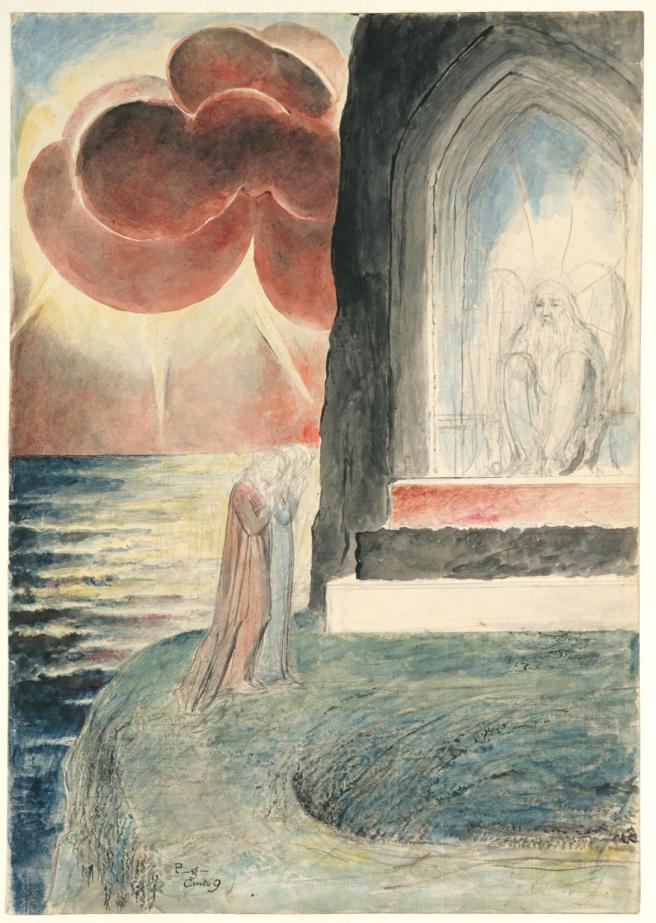

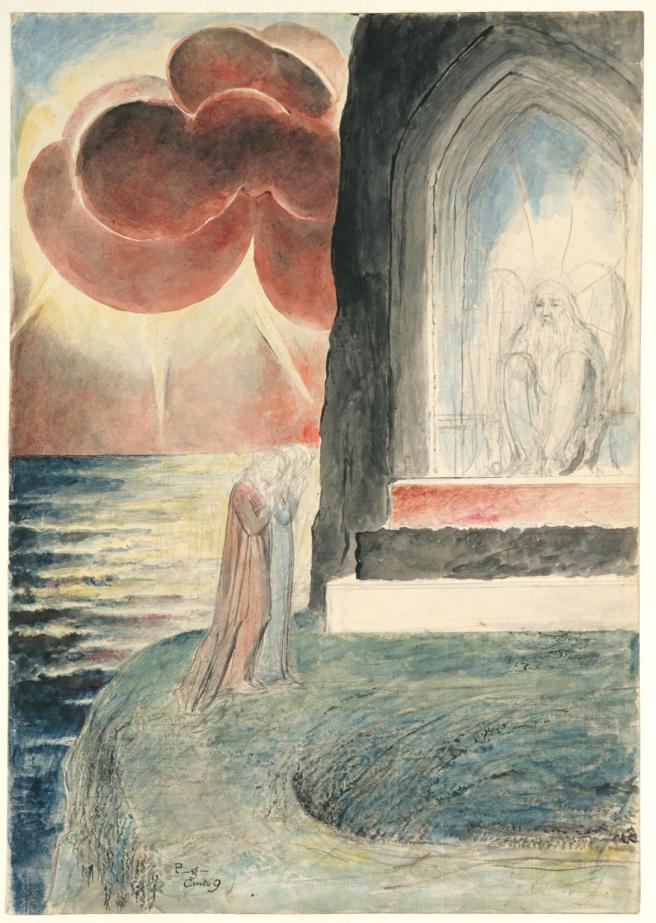

Two illustrations from William Blake’s series on the Divine Comedy, both from Canto 9 (76-114) of Purgatory. I’ve had prints of both on my walls for years – though I just now realize they are less than appropriately mounted over my bar – but thanks to Taschen’s beautiful edition of this series I’m finally able to have everything at hand as visual accompaniment to reading. If only someone would do the same for the Dali series.

I now made out a gate and, there below it,

I now made out a gate and, there below it,

three steps—their colors different—leading to it,

and a custodian who had not yet spoken.

As I looked more and more directly at him,

I saw him seated on the upper step—

his face so radiant, I could not bear it;

and in his hand he held a naked sword,

which so reflected rays toward us that I,

time and again, tried to sustain that sight

in vain. “Speak out from there; what are you seeking?”

so he began to speak. “Where is your escort?

Take care lest you be harmed by climbing here.”

My master answered him: “But just before,

a lady came from Heaven and, familiar

with these things, told us: ‘That’s the gate; go there.’”

“And may she speed you on your path of goodness!”

the gracious guardian of the gate began

again. “Come forward, therefore, to our stairs.”

There we approached, and the first step was white

marble, so polished and so clear that I

was mirrored there as I appear in life.

The second step, made out of crumbling rock,

rough—textured, scorched, with cracks that ran across

its length and width, was darker than deep purple.

The third, resting above more massively,

appeared to me to be of porphyry,

as flaming red as blood that spurts from veins.

And on this upper step, God’s angel—seated

upon the threshold, which appeared to me

to be of adamant—kept his feet planted.

My guide, with much good will, had me ascend

by way of these three steps, enjoining me:

“Do ask him humbly to unbolt the gate.”

I threw myself devoutly at his holy

feet, asking him to open out of mercy;

but first I beat three times upon my breast.

Upon my forehead, he traced seven P’s

with his sword’s point and said: “When you have entered

within, take care to wash away these wounds.”

For the few di color che sanno:

vidi una porta, e tre gradi di sotto

per gire ad essa, di color diversi,

e un portier ch’ancor non facea motto.

E come l’occhio più e più v’apersi,

vidil seder sovra ’l grado sovrano,

tal ne la faccia ch’io non lo soffersi;

e una spada nuda avëa in mano,

che reflettëa i raggi sì ver’ noi,

ch’io drizzava spesso il viso in vano.

«Dite costinci: che volete voi?»,

cominciò elli a dire, «ov’ è la scorta?

Guardate che ’l venir sù non vi nòi».

«Donna del ciel, di queste cose accorta»,

rispuose ’l mio maestro a lui, «pur dianzi

ne disse: “Andate là: quivi è la porta”».

«Ed ella i passi vostri in bene avanzi»,

ricominciò il cortese portinaio:

«Venite dunque a’ nostri gradi innanzi».

Là ne venimmo; e lo scaglion primaio

bianco marmo era sì pulito e terso,

ch’io mi specchiai in esso qual io paio.

Era il secondo tinto più che perso,

d’una petrina ruvida e arsiccia,

crepata per lo lungo e per traverso.

Lo terzo, che di sopra s’ammassiccia,

porfido mi parea, sì fiammeggiante

come sangue che fuor di vena spiccia.

Sovra questo tenëa ambo le piante

l’angel di Dio, sedendo in su la soglia

che mi sembiava pietra di diamante.

Per li tre gradi sù di buona voglia

mi trasse il duca mio, dicendo: «Chiedi

umilemente che ’l serrame scioglia».

Divoto mi gittai a’ santi piedi;

misericordia chiesi e ch’el m’aprisse,

ma tre volte nel petto pria mi diedi.

Sette P ne la fronte mi descrisse

col punton de la spada, e «Fa che lavi,

quando se’ dentro, queste piaghe» disse.

I now made out a gate and, there below it,

I now made out a gate and, there below it,