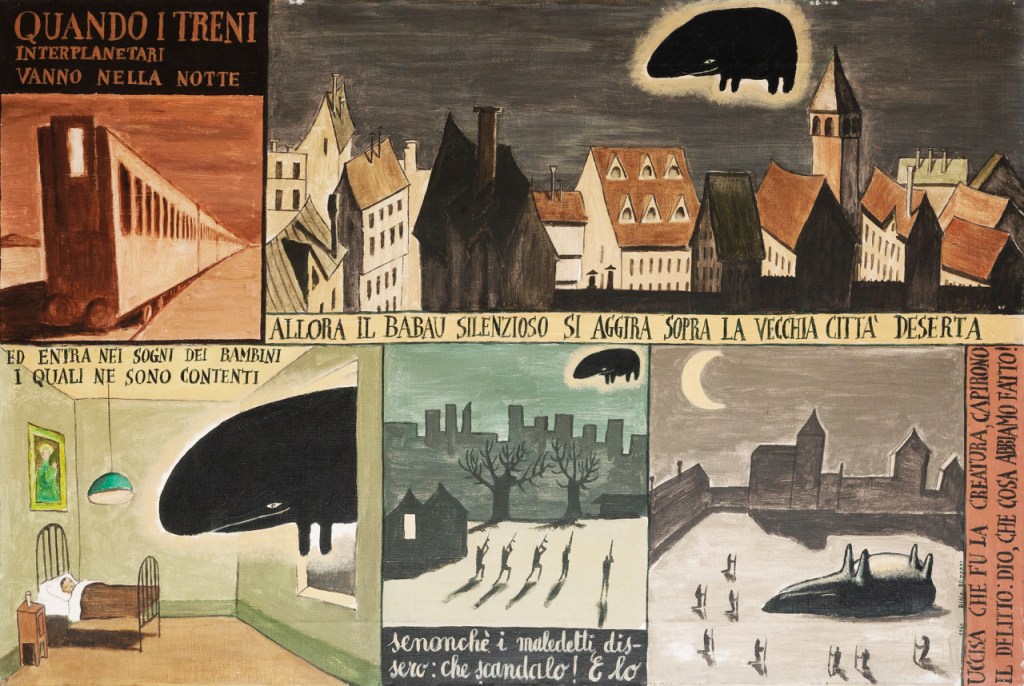

From Dino Buzzati’s The Bogeyman from the recent collection, The Bewitched Bourgeois (originally in Corriere della Sera as FINE DEL BABAU and later reprinted as Il Babau in Le Notti Difficili)

Thus it comes as no surprise that Paudi spoke of the matter [of being visited by the Bogeyman] to several colleagues at the next meeting of the city council. “How can we permit such a disgrace, worthy of the Dark Ages, to continue in a metropolis which boasts of being in the vanguard of contemporary culture? Doesn’t this situation demand decisive action to remedy the problem?”

At first there were brief discussions in the corridors, informal exchanges of opinion. Soon thereafter, the prestige Paudi enjoyed cleared every obstacle from his path. Within two months, the problem was brought before the city council. It stands to reason that in order to avoid ridicule, the agenda of the meeting didn’t contain a word about the Bogeyman. The fifth item mentioned only “a deplorable cause of disturbance that threatens the nocturnal peace of the city.”

Contrary to what Paudi expected, not only did everyone give the matter serious consideration, but his thesis, which might seem obvious, encountered lively opposition. Voices rose to defend a tradition that was as much picturesque as inoffensive yet disappearing in the mists of time. They then proceeded to underscore the utter innocuousness of the nocturnal monster, which was, among other things, entirely silent, and they stressed the educational benefits of that presence. There was one council member who even spoke of “an attack on the cultural heritage of the city” in the event that repressive measures were taken. His speech was greeted with a burst of applause.

In favor of Paudi’s proposal, however, there finally prevailed irresistible arguments which so-called progress always marshals to dismantle the last fortresses of mystery. The Bogeyman was accused of leaving an unhealthy imprint on children’s spirits, of sometimes causing nightmares contrary to the principles of correct pedagogy. Hygienic considerations were also raised: it is indeed true that the nocturnal giant didn’t dirty the city or leave any kind of excrement scattered about, but who could guarantee he wasn’t a carrier of germs and viruses? Nor was anything certain known about his political creed: How could one exclude the possibility that his suggestions, which appeared so simple, if not crude, might conceal subversive plots?

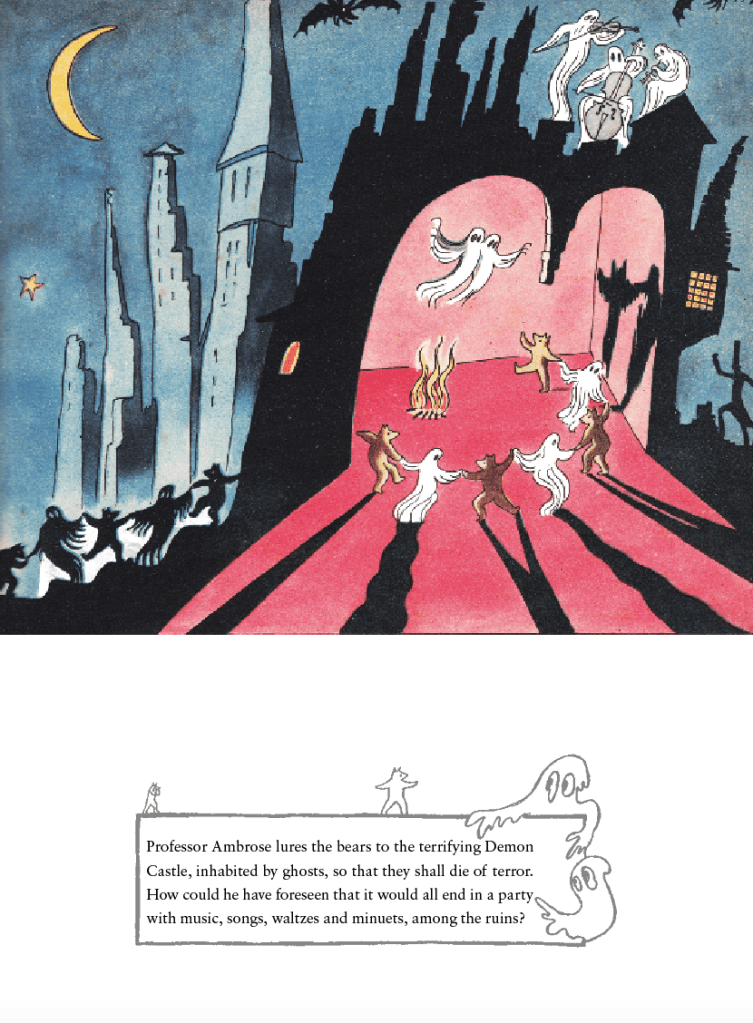

Buzzati did at least a few illustrations of the story sometime around when it was first published (Feb. 16, 1967), though it’s not easy to find firm dates for most of his art. Two of the below are clearly from the story while the third I take to be the babau in a happier day – or maybe it’s just classic cloud watching.

It’s interesting to note the difference between the story and the paintings in the police response to their ultimately slaying the bogeyman. The story has a simple “This is something I’d rather not see a second time” (Una cosa che preferirei non rivedere una seconda volta) while one painting has “God, what have we done!” (Dio, che cosa abbiamo fatto!) and the other the even more emphatic “God, my God, what have we done!” (Dio Dio Mio, che cosa abbiamo fatto!). I tried checked the Corriere archive – which is how I found the original title – to see if the text was different in the first version but was paywalled into continuing ignorance.