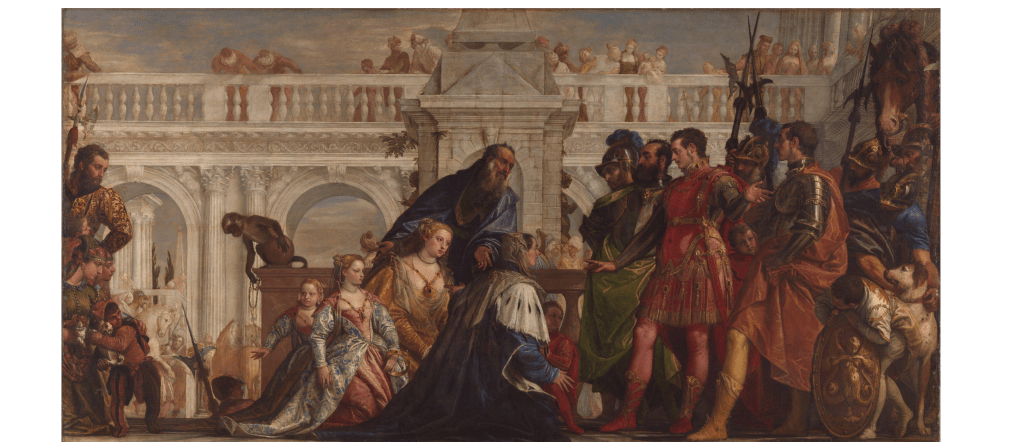

From Goethe’s Italian Journey (October 6):

I visited the Pisani Moretta palace in order to see an exquisite painting by Paul Veronese: the women of Darius’s family are kneeling before Alexander and Hephaestion, the mother kneeling in front takes the latter to be the king, he denies it and points to the right one. According to legend, the artist was well received in this palace and worthily entertained there for some time; in return he secretly painted the picture as a gift, rolled it up, and shoved it under the bed. Truly, it deserves to have had a special origin, for it gives one an idea of this master’s whole worth. His great artistry in producing the most exquisite harmony, not by spreading a universal tone over the whole piece, but by skillfully distributing light and shadow, and equally wisely alternating the local colors, is very visible here, since we see the picture in a perfect state of preservation, as fresh as if done yesterday. For to be sure, when a picture of this kind has decayed, our enjoyment of it is immediately marred, without our knowing the reason.

If anyone wanted to remonstrate with the artist about the costuming, let him just tell himself that the painting is supposed to depict a story of the sixteenth century, and that will settle the whole matter. The gradation from the mother to the wife and daughters is very true and felicitous; the youngest princess, kneeling at the very end, is a pretty little mouse, with a pleasing, headstrong, defiant little face; she does not seem at all ready to accept her situation.

I’d been curious before about the origin story, apocryphal as it of course feels, and found a good summing analysis in a Dec. 2009 Burlington Magazine review by Xavier Salomon. He combines arguments from the work reviewed – Claudia Terribile’s Del piacere della virtu. Paolo Verenese, Alessandro Magno e il patriziato veneziano – and from Nicholas Penny’s National Gallery catalog The Sixteenth-Century Italian Paintings: Volume II: Venice 1540-1600:

The story was a celebrated one and flourished with further embellishments. For Antoine Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville – the first to refer to the story – Veronese had taken refuge in the Palazzo Pisani at Este during a violent thunderstorm; for later writers the painter was recovering from a bad fall from a horse, or escaping the Inquisition. As unlikely as these events can seem, Gould was still dependent on them and his account of the painting was reasonably queried by Cocke. As Nicholas Penny has recently written, ‘it is unlikely that Veronese could have found a suitable canvas waiting for him, unlikely that he would have been able to work on such a large painting in secret, unlikely that he would have rolled it up while still wet, and very unlikely that any bed would have been large enough to conceal it’. Ridolfi mentioned the painting – in the Palazzo Pisani in Venice – in 1648 and, before that, in 1632, Giovanni Antonio Massani had written about it in a letter to Cardinal Francesco Barberini, in which he listed paintings by Veronese that he thought could be on the market. The Family of Darius was for Massani ‘a most beautiful thing, and worthy of a Prince’.

Following Gould’s and Cocke’s speculations regarding the canvas, Claudia Terribile’s impeccable research on the painting – already partly presented in an article – provides key pieces of evidence finally to understand for whom, when and why the Family of Darius was painted. Penny’s recent catalogue of the National Gallery’s Venetian paintings repeatedly cites Terribile’s arguments and pays homage to her archival discoveries. Both Penny and Terribile have produced exhaustive accounts of the painting, which will be of immense help for future studies on the picture and on Veronese. Terribile’s book expands on her previous article and looks at the Family of Darius comprehensively, and Penny’s catalogue entry is so detailed and thorough that it could be published as an independent booklet (much longer than Gould’s of 1978).

Terribile’s book is divided into two parts. The first deals with the original commission, context and history of the painting, while the second focuses on its iconography and meaning. By navigating through the family trees of various branches of the Pisani family, the author identified the patron of the canvas, Francesco Pisani (1514-67), and the painting’s original location, in the Palazzo Pisani at Montagnana, designed by Palladio. This had been tentatively suggested in the 1930s, but Terribile provides further proof to confirm it. When Francesco died, without children, he left his property to his cousin Zan Mattio, and through him to his heirs, whom he wished would assume the first name Francesco in his honour. In 1568 a lawsuit was underway between Zan Mattio and Francesco’s widow, Marietta Molin, who had been effectively disinherited. Zan Mattio complained that Marietta, in an attempt to regain her husband’s property, tried ‘even to remove the canvases and iron [fixtures] of the most precious picture of the story of Alexander the Great’, providing a terminus ante quem for Veronese’s painting. The picture is reasonably dated by Terribile (and by Penny) to the mid-1560s. Francesco must have been an important patron of both Palladio and Veronese, and the contract for Veronese’s early Transfiguration for the high altar of the cathedral of Montagnana was signed in Pisani’s house in 1555.

The post’s title, by the way, is how my grandfather called me over when introducing this painting. The phrase was curious enough to stick with me for thirty years until I finally realized today, thanks to a later portion of Salomon’s article, that it was another bit of his learned humor – the painting’s purchase in 1857 for the then monumental ~£13,500 prompting a parliamentary debate where someone called it a ‘second rate specimen.’ It took a while but the joke finally landed.