A comparison of Beowulf translations – Seamus Heaney, Tolkien, Tom Shippey, and R.D. Fulk. The passage is one of my favorites, Hrothgar’s description of the approach to the home of Grendel and his mother (lines 1355-1379). The title is Tolkien’s take on the – to me – central atmospheric line of the passage – fyr on flode. You’ll notice that Heaney is the only one to avoid the easy alliteration there. I used to regret the choice but I’m no longer sure his isn’t as effective anyway.

Seamus Heaney:

…. They are fatherless creatures,

and their whole ancestry is hidden in a past

of demons and ghosts. They dwell apart

among wolves on the hills, on windswept crags

and treacherous keshes, where cold streams

pour down the mountain and disappear

under mist and moorland. A few miles from here

a frost-stiffened wood waits and keeps watch

above a mere; the overhanging bank

is a maze of tree-roots mirrored in its surface.

At night there, something uncanny happens:

the water burns. And the mere bottom

has never been sounded by the sons of men.

On its bank, the heather-stepper halts:

the hart in flight from pursuing hounds

will turn to face them with firm-set horns

and die in the wood rather than dive

beneath its surface. That is no good place.

When wind blows up and stormy weather

makes clouds scud and the skies weep,

out of its depths a dirty surge

is pitched towards the heavens. Now help depends

again on you and on you alone.

The gap of danger where the demon waits

is still unknown to you. Seek it if you dare.

Tolkien (lines 1132-1152 for his rendering):

… of a father they knew not, nor

whether any such was ever before begotten for him among

the demons of the dark. In a hidden land they dwell upon

highlands wolfhaunted, and windy cliffs, and the perilous

passes of the fens, where the mountain-stream goes down

beneath the shadows of the cliffs, a river beneath the earth. It

is not far hence in measurement of miles that that mere lies,

over which there hang rimy thickets, and a wood clinging

by its roots overshadows the water. There may each night

be seen a wonder grim, fire upon the flood. There lives not

of the children of men one so wise that he should know the

depth of it. Even though harried by the hounds the ranger of

the heath, the hart strong in his horns, may seek that wood

being hunted from afar, sooner will he yield his life and

breath upon the shore, than he will enter to hide his head

therein: no pleasant place is that! Thence doth the tumult

of the waves arise darkly to the clouds, when wind arouses

tempests foul, until the airs are murky and the heavens weep.

‘Now once more doth hope of help depend on thee alone.

The abode as yet thou knowest not nor the perilous place

where thou canst find that creature stained with sin. Seek it

if thou durst!

Tom Shippey:

… Whether he was begotten

by any father from the dark spirits,

they do not know. They dwell, the giant pair,

in the hidden country, wolf-haunted slopes,

windy nesses, dangerous fenland,

where the stream pours down under the dark cliffs

from the mountain, to sink underground.

The mere lies from here not far in miles.

Over it there hang frosty-bound groves,

fast-rooted woods overshadow the water

Every night you can see a dreadful sight there,

fire in the flood. No child of men

is so wise as to know what lies beneath.

Although the proud-horned stag, the heath-treader,

is pressed by hounds, hunted from afar,

and seeks shelter in the wood, he will on the shore

give up life and breath, before, to save his head,

he will plunge in. That is an uncanny place.

When the wind stirs up foul weather,

the tossing waves rise dark to the clouds,

until the air drizzles, the heavens weep.

Now the decision is up to you alone.

You do not know the land, the dangerous place

where you can find the sinful creature.

Seek if you dare!

R.D Fulk’s prose version:

they knew of no father, whether any mysterious creatures had been born before him. They inhabit hidden country, wolf-hills, windy crags, a dangerous passage through fen, where a cascading river passes down under the gloom of cliffs, a watercourse under the earth. It is not far in miles from here that the pool stands; over it hang frost-covered groves, firmly rooted woods overshadow the water. There every night a dire portent can be seen, fire on the flood. There lives no offspring of men so well informed that he knows the bottom. Even if a heath-roamer beset by hounds, a hart firm of antlers, makes for the forest, driven far in flight, it will sooner give up the ghost, its life on the bank, than enter and save its head; that is not a pleasant place. There the tossing waves mount up dark to the clouds when the wind stirs up ugly storms, until they choke the air and the heavens weep. Now the course of action is again dependent on you alone. You are not yet acquainted with the region, that dangerous place where you can find the one who is the offender; go look if you dare!

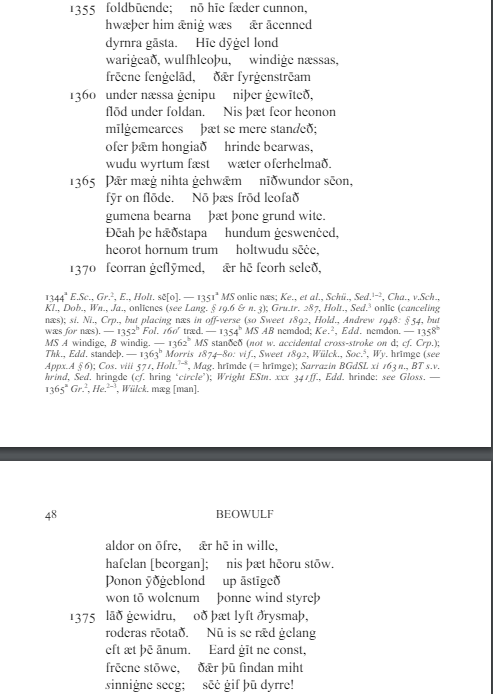

And the original from the standard Klaeber’s Beowulf (4th edition). Unsurprisingly WordPress doesn’t care for the unique Old English characters so a screenshot will have to suffice: