From Shakespeare’s Pericles, Prince of Tyre (4.2, the firmly Shakespearean portion of the play beginning at act 3):

I warrant you, mistress, thunder

shall not so awake the beds of eels as my giving

out her beauty stir up the lewdly-inclined.

The clear phallic play aside, the Arden note adds:

If not a proverb – Dent questions (?T276) ‘Thunder looses beds of eels’ – this was certainly a common zoological belief, appearing in Marston’s Scourge of Villainy (1598) and George Wither’s Abuses Stripped and Whipped (1613).

Dent in both Shakespeare’s Proverbial Language and the more catchingly titled Proverbial Language in English Drama Exclusive of Shakespeare, 1495–1616 is cagey about asserting the proverb despite compiling four other instances of the belief. In the former he cites:

1598 Marston Satire 7.78 – They are naught but Eeles, that never will appeare, / Till that tempestuous winds or thunder teare / Their slimie beds.

1613 G. Wither Abuses ed. 1863 168: Let loose, like beds of eels by thunder.

cl620 (1647) Fletcher & Massinger, False One 4.2.200f.: I’ll break like thunder / Amongst these beds of slimy Eeeles.

And in the latter adds:

1615 S.S. Honest Lawyer II C3v: Shall we cling, like a couple of Eeles, not to bee dissolv’d but by Thunder?

None of this addresses the question of the origin of the idea of eels fearing/stirred up by thunder, which is what I mainly cared about. I don’t have a definite answer, but I do have a logical chain. We begin with Pliny, as anyone seeking answers on odd beliefs about animals should do (Natural History 9.38):

Eels live eight years. They can even last five or six days at a time out of water if a north wind is blowing, but not so long with a south wind. But the same fish cannot endure winter in shallow nor in rough water; consequently they are chiefly caught at the Pleiads, as the rivers are then specially rough. They feed at night. They are the only fish that do not float on the surface when dead. There is a lake called Garda in the territory of Verona through which flows the river Mincio, at the outflow of which on a yearly occasion, about the month of October, when the lake is made rough evidently by the autumn star, they are massed together by the waves and rolled in such a marvellous shoal that masses of fish, a thousand in each, are found in the receptacles constructed in the river for the purpose.

I’ve edited the above to translate circa verginias as ‘at the Pleaids’ rather than ‘at the rising of the Pleaids’ since I think this confuses the issue.

The Pleiades were associated in the ancient world with storms at both their rise in Spring (April-ish) and especially their setting in Fall (Oct-Nov). So Hesiod in Works and Days (615-622):

When the Pleiades and Hyades and the strength of Orion set [in October], that is the time to be mindful of plowing in good season. May the whole year be well-fitting in the earth. But if desire for storm-tossed seafaring seize you: when the Pleiades, fleeing Orion’s mighty strength, fall into the murky sea, at that time [in November] blasts of all sorts of winds rage; do not keep your boat any longer in the wine-dark sea at that time

Later Ovid in Heroides (18.187):

What when the seas have been assailed by the Pleiad, and the guardian of the Bear, and the Goat of Olenos? Either I know not how rash I am, or even then a love not cautious will send me forth on the deep

And a last instance in Statius’ Silvae (3.2.71):

Hence raging winds and indignant tempests and a roaring sky and more lightning for the Thunderer. Before ships were, the sea lay plunged in torpid slumber, Thetis did not joy to foam nor billows to splash the clouds. Waves swelled at sight of ships and tempest rose against man. ’Twas then that Pleiad and Olenian Goat were clouded and Orion worse than his wont.

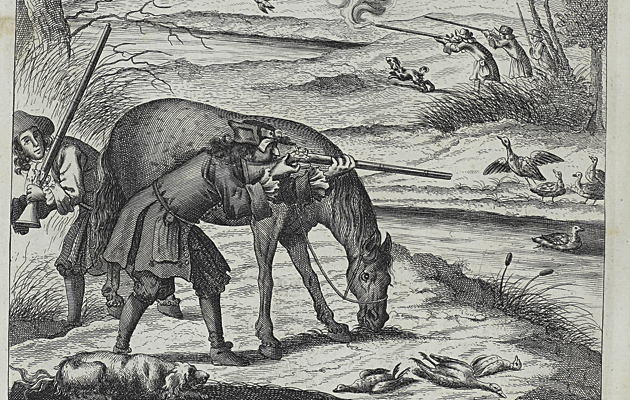

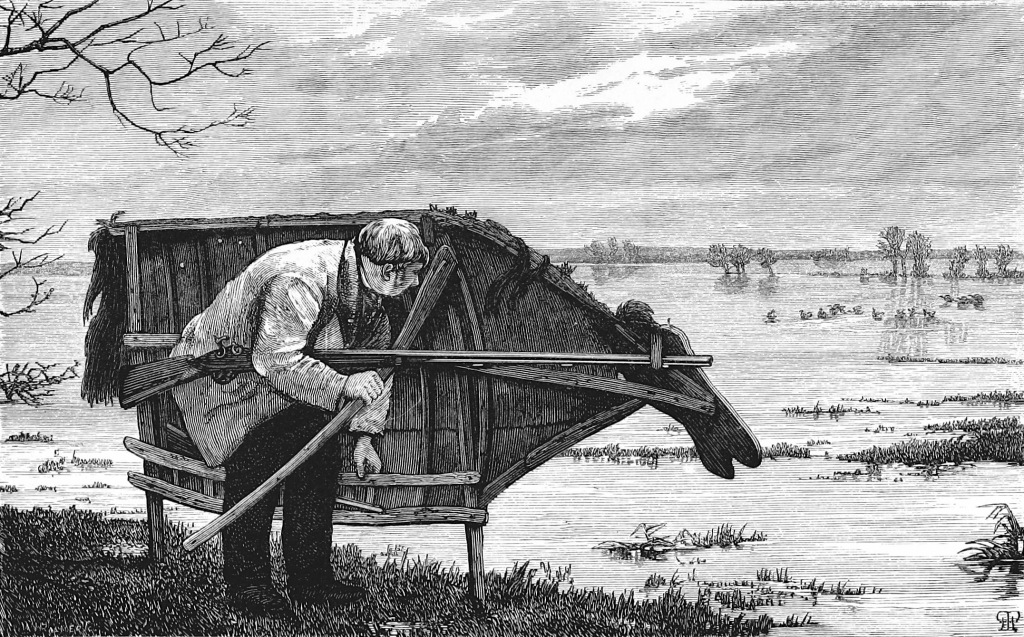

It doesn’t seem a far leap to take that Pliny’s reported pattern of eel behavior and eel hunting season, whether scientifically accurate or not, was understood as connected to the rising or setting of the Pleiades and so to the stormy season. Hence by shorthand approximation to thunder generally. And so eels, unable to deal with storms or the rough water that follow, were viewable as loosed from bed by thunder.

To all this my vanity adds a much later reference in the opening of Robert Browning’s Old Pictures in Florence. I was proud of this as altogether my own but in due diligence checking the most recent edition of John Marston’s poetry (The Poems of John Marston ed. Arnold Davenport) I found a previous editor of the same (Bullen) had also pointed out the quote, taking it as Browning reporting a piece of ‘Italian folk-lore’:

The morn when first it thunders in March,

The eel in the pond gives a leap

I sometimes feel bad about doing these things on work time but I work for a university so it should all wash out as research.