From Sir Leslie Stephen’s essay on Sir Thomas Browne in Hours in a Library (first essay in vol. 2 of my 4 vol. edition – a different one is on Gutenberg):

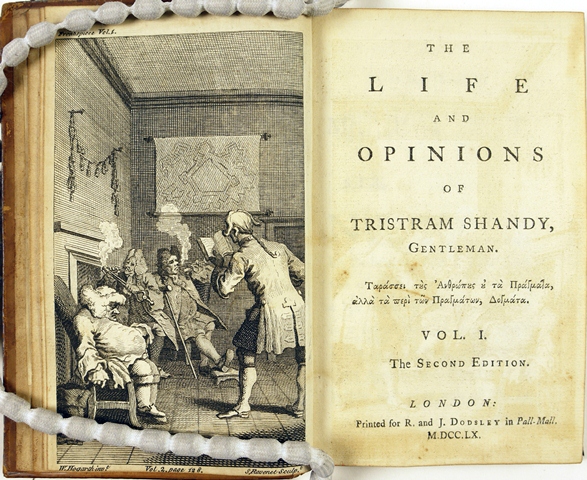

A mind endowed with an insatiable curiosity as to all things knowable and unknowable; an imagination which tinges with poetical hues the vast accumulation of incoherent facts thus stored in a capacious memory; and a strangely vivid humour that is always detecting the quaintest analogies, and, as it were, striking light from the most unexpected collocations of uncompromising materials: such talents are by themselves enough to provide a man with work for life, and to make all his work delightful. To them, moreover, we must add a disposition absolutely incapable of controversial bitterness; ‘a constitution,’ as he says of himself, ‘so general that it consorts and sympathises with all things;’ an absence of all antipathies to loathsome objects in nature, for all theological systems; an admiration even of our natural enemies, the French, the Spaniards, the Italians, and the Dutch; a love of all climates, of all countries; and, in short, an utter incapacity to ‘absolutely detest or hate any essence except the devil.’ … A man so endowed … is admirably qualified to discover one great secret of human happiness. No man was ever better prepared to keep not only one, but a whole stableful of hobbies, nor more certain to ride them so as to amuse himself, without loss of temper or dignity, and without rude collisions against his neighbours. That happy art is given to few, and thanks to his skill in it, Sir Thomas reminds us strongly of the two illustrious brothers Shandy combined in one person. To the exquisite kindliness and simplicity of Uncle Toby he unites the omnivorous intellectual appetite and the humorous pedantry of the head of the family.